We hadn’t planned on visiting the Keats-Shelley Memorial House. In fact, it was a complete accident that we stumbled upon it as we approached the Spanish Steps (where every other tourist in Rome seemed to be going that day!). Housing a treasure greater than a pile of old stones, I couldn’t believe my luck when I first saw the sign hanging next to the great steps. Even my husband, dubious at this underwhelming entrance I was pulling him towards, squealing and smiling like I’d found the holy grail – yes, even he emerged from the building afterwards thankful and happy that we’d found this unassuming little gem.

The crowded Spanish Steps (left) may overshadow the Keats-Shelley Memorial (right) in physical presence, but I know which will stay with me for longer. It was also great being able to have the whole place to ourselves – a nice change from the throng of tourists.

What was inside that made it the highlight of our day, you ask? Well, I’ve been a poet, and a poetry-lover, for a long time. It’s been 20 years; before I was a blogger, before the internet even, Keats, Shelley, Byron – they were my inspiration to write, my friends and mentors, albeit from beyond the grave. So you can imagine what a reunion it was to have found my comrades (or at least, a tribute to them), across the ocean and completely by chance – a lovely surprise on a warm, Italian summer afternoon. (On the same trip, we visited Oscar Wilde’s tomb – quite a literary pilgrimage, don’t you think?)

Inside, the building is an experience in itself, even if you’re not a fan. Furnished in dark timber, and lined with books from floor-to-ceiling, the scent of a library overwhelms the senses – wood and paper aged over hundreds of years, as intoxicating as the fragrance of a good wine matured in oak. But there is something else – a feeling that tingles the nerves, something that lurks in the still, silent air; a presence that can only be felt, not seen. It is such a privilege to touch the same walls as he did, to walk those same steps, and look out those same windows. Perhaps it’s him we feel, looking over our shoulders in sadness.

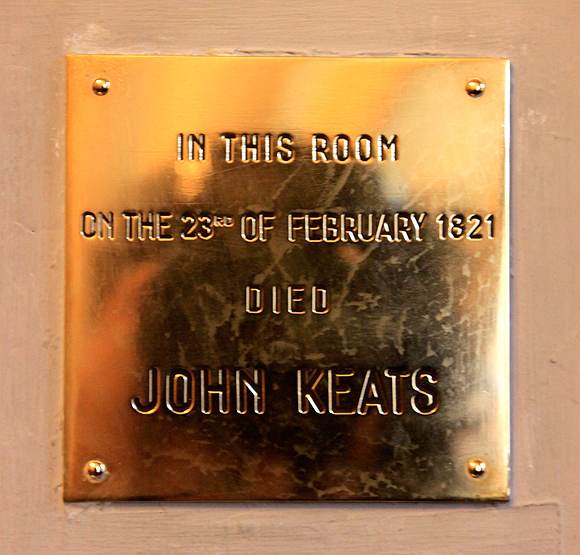

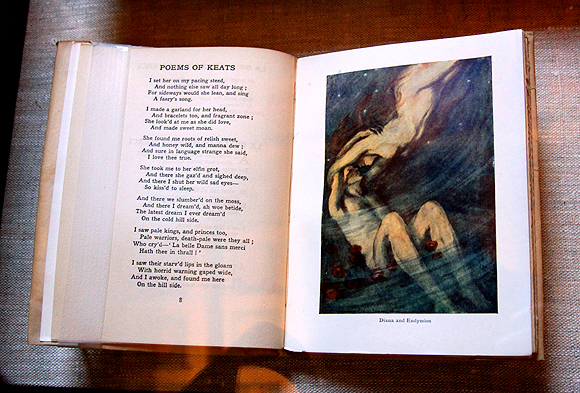

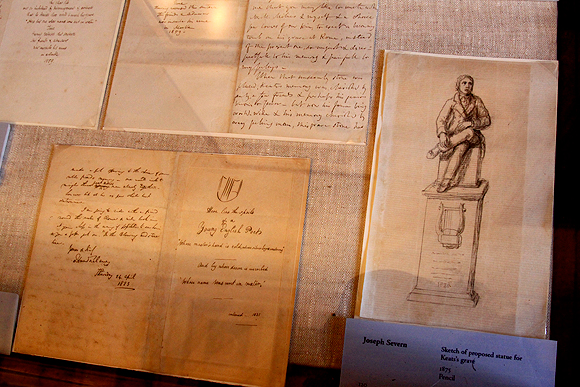

In his later days, Keats, sick with consumption (tuberculosis), intended to move to Rome in the hopes of curing his illness with the warm Italian weather. England’s climate was unforgiving, so he boarded a ship in search of summer. Unfortunately, it turned out that his ship was delayed so much that he arrived in Rome too late – it was the middle of winter. The building would have been gloomy and cold, quite different to this day, with light streaming in from the large windows, a light breeze gently stirring the sheer, cloud-like curtains. The building, it turned out, was the final haven for Keats – he fell victim to his sickness and wheezed his last breath in a little room on the second floor. That floor is now converted into a library and a memorial to Keats and his peers. Not only can you visit the room where he died, but you can also read his last letters, exquisitely hand-written and encased in glass.

A close replica of the bed that John Keats die in. (Italian law decreed that everything in Keat’s room be burned to stop the spread of infection. As a result, the furniture in the room has been restored in the style of the period.)

A portrait by Joseph Severn, Keat’s close friend, who nursed him in his dying days. The scrawl beneath it reads, “28 January 1821, 3 o’clock in the morning. Draw to keep me awake. A deadly sweat was on him all this night.”

Joseph Severn spent years planning to erect a great tombstone for Keats. These sketches and notes are as far as it got – unfortunately it never eventuated.

These artifacts have survived the ravages of time, as well as the great wars. American Poet Robert Underwood Johnson began an initiative to preserve the apartments in the early 1900s – it was later bought by the newly formed Keats-Shelley Memorial Association, and converted into the Keats-Shelley Memorial House. During WWII, all signage was removed in an attempt to protect it from the Nazi’s, and some of the contents hidden in boxes at the remote Abbey of Monte Cassino. When the Abbey came under attack, the boxes were moved again, and eventually restored in 1944, when the Allied forces liberated Rome.

If only Keats had known when he was alive that his legacy would live on thanks to the kindness of strangers. Like many artists, he never achieved the fame during his life that he did after his death. A letter to his fiance in his final days is mournfully regretful:

“I have left no immortal work behind me – nothing to make my friends proud of my memory – but I have lov’d the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time I would have made myself remember’d.”

But it is some consolation to know his peers – and future generations – thought differently of him. While his career spanned only six years, he created a universe of literature that is studied in schools and universities the world around.

A passage from one of my favourite poems, “Ode to a Nightingale“, by John Keats:

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

In fact, several poets of his time referenced him in their work. Seven months after his death, his dear friend (and highly esteemed poet of the same era – although you might know his wife a little better, the author of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley) Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote, in a poem dedicated to Keats,

The loveliest and the last,

The bloom, whose petals nipped before they blew

Died on the promise of the fruit.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

The Keats-Shelley Memorial House is open Monday to Saturday, 10.00am – 6.00pm, admission is €5 for adults. It closes for lunch (1.00 – 2.00pm), every Sunday, and on the following dates: 8th December, 23-31st December, and 1st January.

Enjoyed this post? Read the next post from this series: “A Honeymooner’s Guide to six weeks in Europe” now!

Enjoyed this post? Read the next post from this series: “A Honeymooner’s Guide to six weeks in Europe” now!